Posts tagged with Background

On Wednesday August 30, 1665, the diarist Samuel Pepys ran into his parish clerk and asked how the plague was progressing within their parish. To his dismay, the clerk “told me it encreases much, and much in our parish.” Worst of all, the clerk admitted that the plague was so bad that he had falsified his weekly reports of parish plague deaths: “for, says he, there died nine this week, though I have returned but six.” Whether or not Pepys castigated the parish clerk in person, he recorded his condemnation of such “a very ill practice” in his diary. The numbers within the bills of mortality were a vital public health guide during plague outbreaks and it was imperative for them to be as accurate as possible.

Found Dead? Unknown Causes of Death in the Bills of Mortality

The greatest purpose of the Bills of Mortality is to enumerate death, first due to plague then expanding over the years to include other causes. However, there are some gray areas where Searchers lacked the necessary information to provide a label. In these instances, the records reflect the phrase “found dead.” This label carried a wide range of ages and deaths and was listed with a basic description of the deceased person and how they were found.

Why is There Bread in the Bills?

We have talked on the blog about some of the datasets we are transcribing from the Bills of Mortality - the counts of death by parish, causes of death, and christening and burial numbers. Some of the bills have even more information on them: the price of bread (and eventually other foodstuffs). But why would state-mandated bread prices be included in the Bills of Mortality? To find out, we need to look more closely at the role of bread in early modern England.

A Parish By Any Other Name

The Bill of Mortality from Christmas week in 1664 reports that three people died in the parish of St Foster. But fifty years later, there were happily no Christmas deaths in the parish of St Vedast—or rather, the parish of “St Vedast alias Foster.” Because the parish of St Vedast is the parish of St Foster. Welcome to the complex world of early modern parish names.

Given that our sources were published over the course of centuries, it’s hardly surprising that the names of some of the parishes in the bills changed over time. It does, however, present a bit of a challenge for our project since transcribers must be able to match the names in the bills to the names on the transcription form. And even if we were to change the names on the transcription form to accommodate changing parish names, analyzing bills of mortality over time still requires us to know whether a parish listed on a bill in 1582 is the same as a parish listed in a bill in 1752. Our solution has been to create a master list of the parish names, which includes the parish names we use on the transcription forms along with variant names that transcribers might encounter over time. These variant names are then included both in the transcription form and the detailed guidelines for our transcribers.

"Within the Bills": EEBO and the Early Modern London Metropolis

One of the more helpful digital databases for the study of early modern history is Early English Books Online (EEBO), which contains images of most of the surviving books printed in England between 1473 and 1700. It builds upon the cataloging work of 19th-century bibliographers and began its life as a collection of microfilm in the late 1930s and 1940s before being digitized at the turn of the twenty-first century.1 Because its focus is on books rather than broadsides or bills, EEBO only contains a small fraction of the early modern Bills of Mortality but a keyword search for the bills still turns up almost 500 results. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these are largely publications that mention the bills rather than the bills themselves. However, it is interesting that these publications are not discussing the bills as a source of quantitative data on mortality. Instead, they are using the bills as a synonym for a place: the city of London and its suburbs.

Parishes and Extra-Parochial Places

The main organizational unit behind the London Bills of Mortality is the parish: a religious administrative unit usually consisting of one or more churches, their associated staff, and all Christians living within the geographical bounds of the parish. The parish clergy christened, married, and buried their parishioners and—starting in the sixteenth century—the parish clerk kept a register of those events. The burial numbers would eventually form the basis of the bills, with christenings added later.

Confusion of Calendars

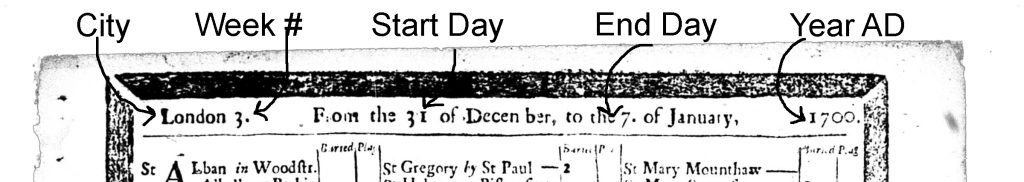

One of the first things a Bill of Mortality tells the reader is the date. The bill (partially) pictured below covers mortality data for the city of London, in the 3rd week of the current bills’ year, which ran from the 31st of December to the 7th of January in the year 1700 AD (from the Latin, Anno Domini, which was often translated into English as the Year of the Lord).

Figure 1. Annotated bill of mortality with arrows pointing to the city name (London), bill number (3), start and end days (‘From the 31st of December to the 7th of January’) and AD year (1700).

The London Bills of Mortality

Plague epidemics were a recurring threat in late medieval and early modern Europe. While plague could and did strike anywhere, the most well-documented epidemics were often in cities. Responses varied across time and space, as city leaders and other political authorities attempted to avoid contagion, contain the sick, and understand the scope of the threat plague currently posed to their lives and their livelihoods. These responses included the creation of lists: lists of people sick with plague, lists of cities infected with plague, and–starting in the sixteenth century–lists of the number of people who had died of plague.