| September 12, 2022

Why is There Bread in the Bills?

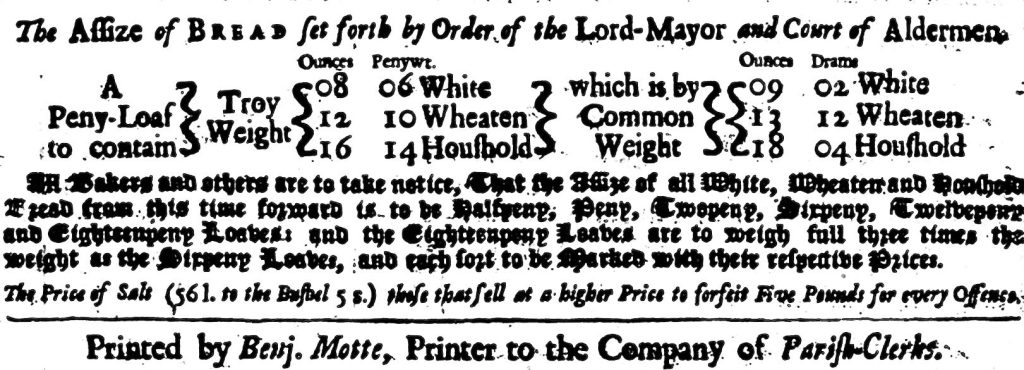

We have talked on the blog about some of the datasets we are transcribing from the Bills of Mortality - the counts of death by parish, causes of death, and christening and burial numbers. Some of the bills have even more information on them: the price of bread (and eventually other foodstuffs). But why would state-mandated bread prices be included in the Bills of Mortality? To find out, we need to look more closely at the role of bread in early modern England.

Figure 1. Bill of Mortality 1701 week 17.

Regulating the price of bread?

The price of bread had been set in England through the Assize of Bread for centuries before the Bills began. In fourteenth century London, “four honest men” would annually buy wheat and have it baked into bread to assay, or test, the quality and weight of bread being baked in the city. These bread assayers were assessing bread in the same way that other assayers tested the quality of gold and silver.

By testing the bread in this way, assayers were not only ensuring that bread sold in London was consistently made but - more importantly - that the bread was consistently priced. The later point was particularly critical in the early modern era when the increasing cost of goods was a growing concern. The Assize of Bread sought to reduce the risk of potential price gouging of Londoners who sought to purchase bread from a bakeshop or market rather than make it in their own homes (Seabourne).

Why bread and not other things?

Bread was a major part of the diet of people in early modern England. Thomas Moffat, a sixteenth-century physician, described bread as “necessary to the life man.” This was particularly true of the laboring classes, who would have eaten bread as part of most of their daily meals. Historian Craig Muldrew describes food as the “essential source of energy for the early modern economy” (Muldrew, 3) and bread was a key component of that energy source. Muldrew’s tables of diets in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries show that bread generally provided at least twenty percent of a person’s daily caloric intake. He estimates that most adult laborers ate - or, at least, needed to eat - one pound of bread each day (Muldrew).

The only other foodstuff regularly included in the Bills was a report on the price of salt. More than just a way of improving the flavor of food, salt was a vital resource for preserving meat (Buxton).

But didn’t people bake their own bread?

Some people did. However, baking bread in the early modern era was a complicated matter. Anyone who started baking bread during the recent COVID-19 pandemic might have an idea of the labor involved, but imagine it without a stand mixer or an oven you can set to a specific temperature with the turn of a dial. Bakers, professional or not, had to get their ovens up to temperature by setting fires inside the oven to get it up to the right temperature, and only baking the bread after the fire was out. Even in the countryside, there sometimes were communal bread ovens that people could use, rather than every household having their own. According to Anthony Buxton, only about a quarter of households in early modern London had the tools to do their baking at home (Buxton).

In London, where there was a higher concentration of industry and people, bakers and bakeshops became both more common and more frequented by people opting for the convenience of premade bread. As the demand for pre-made bread grew, London saw the professionalization of bakers and establishment of competitive bakery businesses which sold their wares in shops or in the city markets (Kernan). A London baker might be a member of the Worshipful Company of Bakers, a guild very much like the Worshipful Company of Printers who were responsible for the production of the Bills of Mortality.

Why is bread on the Bills?

There is no clear evidence as to why the information about the prices of bread and other foodstuffs were eventually included on the Bills. However, despite the fact that the Assize of Bread predated the Bills of Mortality, it makes sense that they would be published on the same broadside.

The Bills were public information sheets providing important, numerical news for people in London. The set prices of bread and other commodities were key public information just like the plague case counts. Publishing all of this information in one place provided the London public with a single quick reference for all of their quantifiable news.

Works Cited

- Anonymous. The Severall Places where You May Hear News. The Map of Early Modern London, Edition 7.0. Ed. Janelle Jenstad. Victoria: University of Victoria. Accessed May 05, 2022. mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/SEVE1.htm.

- Buxton, Antony. “Foodstuff Provisioning, Processing and Cooking.” In Domestic Culture in Early Modern England (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2015), 95–133. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt17mvj8f.10.

- Kernan, “From the Bakehouse to the Courthouse: Bakers, Baking, and the Assize of Bread in Late Medieval England”, Food & History vol 12, no 2 (2014) https://doi.org/10.1484/J.FOOD.5.108966

- Muldrew, Craig. Food, Energy and the Creation of Industriousness: Work and Material Culture in Agrarian England 1550-1780 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Seabourne, Gwen. 2006. “Assize Matters: Regulation of the Price of Bread in Medieval London.” Journal of Legal History 27 (1): 29–52. doi:10.1080/01440360600601862.