| August 16, 2022

Chimneys and the Great Storm of 1703

In late November of 1703, a “great storm” or hurricane struck the British Isles. Bad weather began a few days before the heart of the storm made landfall on November 26th, spawning tornadoes, ripping off roofs and chimneys, and destroying entire fleets. One of the most famous tragedies of the storm happened on the Goodwin Sands, a deadly sandbank off the coast of Kent. At least 53 ships were wrecked on the sandbank and over 2,000 men died just six miles from safety.

Figure 1. Ships being tossed about by a storm at sea.

The death and destruction continued throughout southern England, including in the capital city of London. As one contemporary report tells:

IN the City of London many Houses have been uncovered, almost in every Street; great quantities of Lead blown off the Churches, Halls, and Houses; Stacks of Chimneys, and Roofs of Houses blown down; and some Spires broken: And in the adjacent Fields, Trees tore up by the Roots. And several Persons killed in and about the City. In the River the Lighters were forced from their Anchors; and Barges laden with Corn and Meal sunk (M.D. 1703, 19).

While this report gives a sense of the widespread destruction, what it doesn’t do is give any details on the “several Persons killed in and about the City.” To get that, we turn to the London Bills of Mortality.

The Bills of Mortality further reveal the extent of the destruction that the storm of 1703 wreaked on the city of London by telling us how many people died, their cause of death, and in what parish their death was recorded. The most common cause of death during a storm of this size was from the partial or total collapse of buildings, especially chimneys and roofs. These causes of death were recorded in three sets of bills around the time of the hurricane. The first bill records these causes of death from November 23rd to November 30th, which was when the storm was at its peak. Ten deaths were recorded in this bill; eight from collapsed chimneys and two from the collapse of a house. A factor that needs to be considered while analyzing these bills is that since this was a major weather event that prevented people from venturing outside, it is possible that some deaths that occurred during this week could not be reported in time for printing, and were delayed until the next week’s publication. This means that some of the eleven deaths recorded on the second bill, from November 30th to December 7th, could have happened the week prior.

Of the eleven deaths on the second bill, six were from collapsed chimneys, two from the collapse of houses, one from the collapse of a roof, one from accidentally falling in the street, and one from the fall off of a roof. It is possible that falling in the street was not a direct result of the storm, but we believe it to have been a fall associated with storm-related rubble. In addition, the fall off of a roof was reported as a fall “from the Eaves of an House at the Temple,” a law school that was not located in a particular parish, rather existing as its own extra-parochial place. Since its location cannot be recorded using our extant parish shapefiles (which exclude extra-parochial places) and there is no conclusive evidence that this death was storm related, we do not include this death in our analysis.

The third bill is from the week after the storm, December 7th to December 14th. It is included in this analysis because there are two causes of death on the bill that resemble the deaths on the previous bills. Just like our speculation that some deaths were delayed in printing because of the inclement weather and salvage effort, this bill may also have some delayed information. The two that stood out among those recorded were one death from a collapsed chimney and the other “by the fall into the hold of a ship.” Either of these deaths has the possibility of being storm related, but since it was recorded a week after the storm ended, it is difficult to conclusively say that they were, especially since they were listed with a few other deaths such as a murder and being burnt. Collapsed chimneys were the primary cause of death related to the storm that were published in the Bills of Mortality and so is the more likely of the two to have been storm related. But a death by falling into the hold of a ship would also be likely after a hurricane. There were over eight thousand sailors who drowned at sea, and in the Thames there were also barges and other small boats that were destroyed in the gale. Many drowning deaths and other water-related accidents are recorded in the bills at other times and in other years, because of the high traffic of boats and other maritime businesses on the river, but since this death is so close to the hurricane, it is likely that it was related to salvage efforts in the aftermath of the storm. Unfortunately, this death did not have its location recorded in the bill and also cannot be included in our analysis, though we believe it is likely a storm related death.

Though we do not know for sure from the bills alone if all these deaths were storm related, a 1704 book by British author Daniel Defoe offers some further insight. Titled The Storm, the book is a compilation of first hand accounts about the hurricane. Defoe references the bills when discussing the aftermath, “our weekly bills of mortality gave us an account of twenty-one [deaths]; besides which were drowned in the river, and never found; and besides above two hundred people very much wounded and maimed [as result of the storm]” (Defoe 1855, 301). From these three bills, we found a total of twenty-three deaths that are (potentially) related to the hurricane. The difference can be accounted for either by Defoe not counting the third bill (two deaths) or by Defoe excluding the two falls (in the street and on the ship) from his totals.

Calculating the number of deaths that can actually be attributed to a storm is difficult, even today, so these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt. Were there missing persons whose deaths were never recorded, such as deaths in the river whose bodies were swept out to sea? Besides delays in printing deaths (bills only being printed weekly not daily) and potential delays in reporting deaths due to the chaos of the storm, were there people who were fatally injured but lingered for additional weeks and eventually had deaths recorded in ways that are not recognizably related to the storm? Were there people who died of other natural causes who wouldn’t have died if there hadn’t been a storm? These are questions that can’t be answered from the bills alone and require further archival research to confirm or deny our speculations.

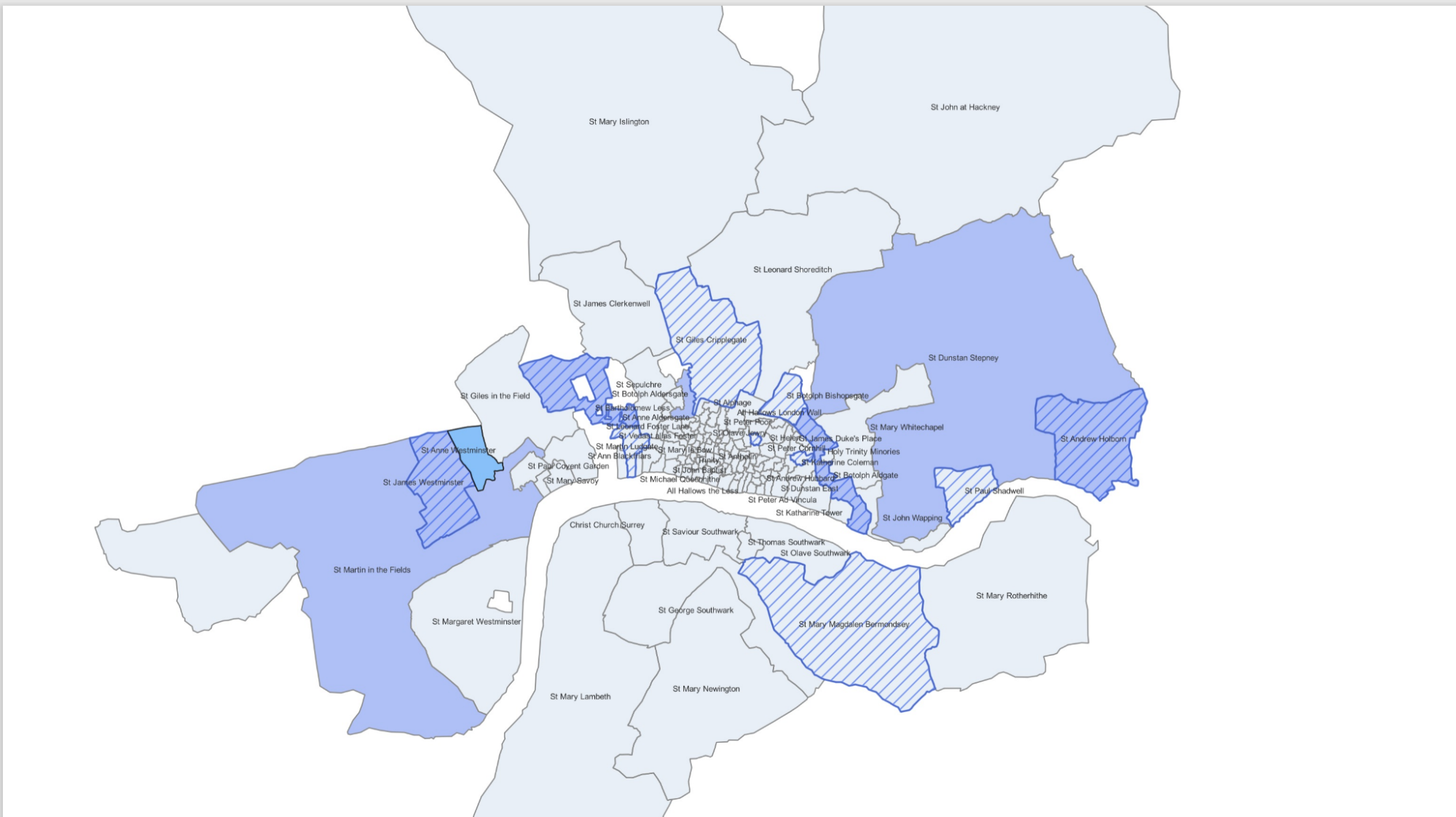

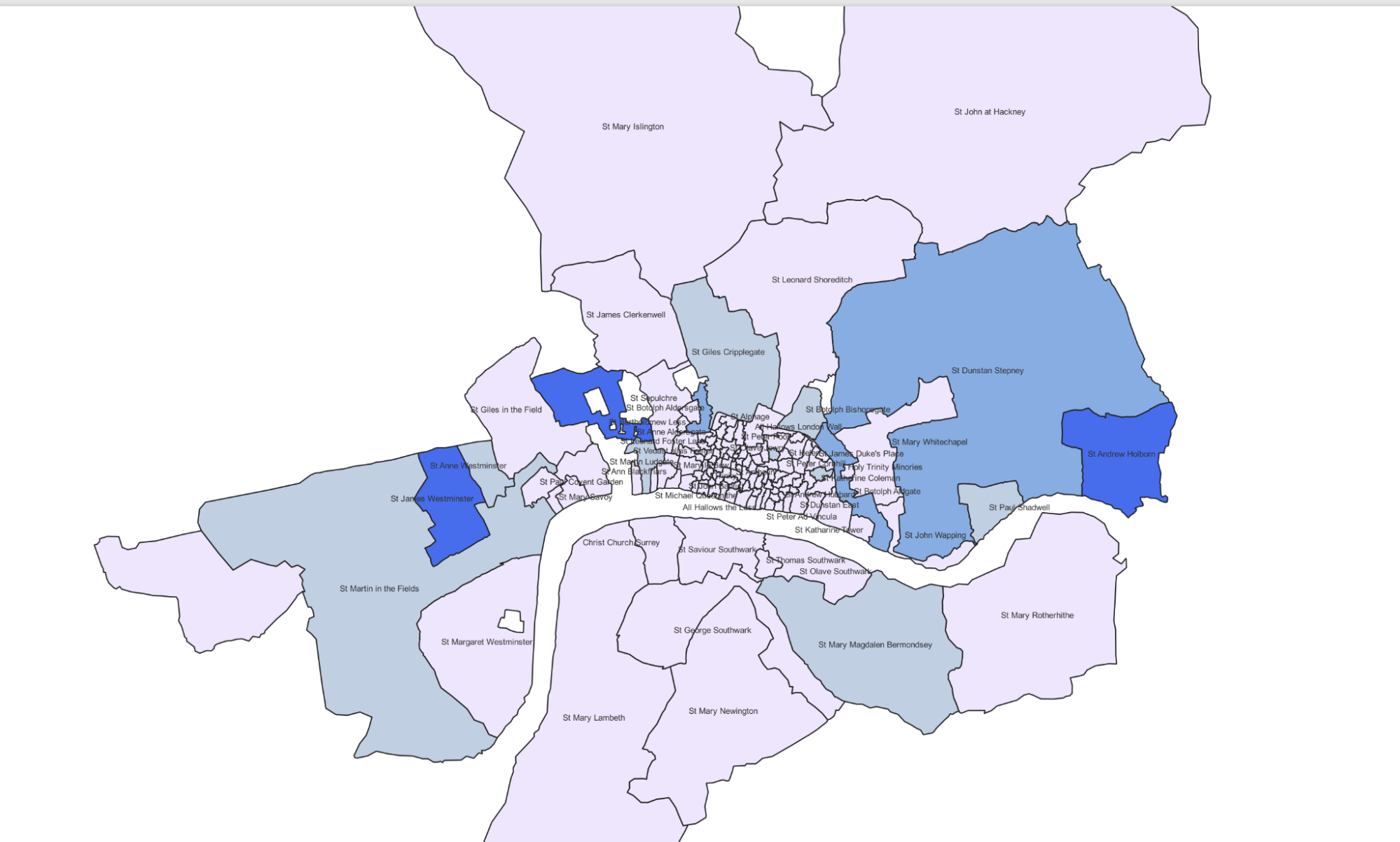

One thing the bills can tell us, however, is where people were dying throughout the city. This is because location data has been recorded for many of the deaths we have identified as storm related. These locations offer another way to analyze the deaths related to the storm. In the first map, we see deaths by week reported. Pale blue is no deaths in any of our three weeks, light blue is one or more deaths in “week 50” of 1703 (November 23-30), dark blue with stripes is week 51 (November 30-December 7), and turquoise blue is week 52 (December 7-14). In the second map, we see deaths by parish for weeks 50-52 summed. Purple is no deaths, light blue is 1 death, medium blue is 2 deaths, and dark blue is 3 deaths.

Figure.

Figure.

As we can see on the map, the majority of the deaths were recorded in the parishes “without the walls”—that is, outside the London Wall—with the exception of St. Bennet Fink and St. Katherine Coleman. The visualization provided by the location data from the bills tells us that the highest number of deaths occurred in the parishes furthest from the center of London. This geographic pattern can partly be explained by the infrastructure and rebuilding of the city after the Great Fire of London in 1666. The areas of London that burnt down in the fire were mostly contained inside the London wall, a Roman structure that circled a “mass of medieval streets, lanes and alleys,” where the houses were mostly built of timber (Mortimer 2017, 10). These wooden medieval houses which were packed together inside the London wall were one of the reasons the fire spread so quickly (Mortimer 2017, 21). After the fire, the areas that were burnt down had been almost entirely rebuilt in brick. This shift to newer, more durable infrastructure in the parishes inside the London wall meant that these houses would stand up better to other natural phenomena, such as the high winds associated with hurricanes. As the maps show, the area inside the London wall has the least number of reported deaths due to the storm, and it is possible that the reconstruction of the city after the fire of 1666 plays a role in these low numbers.

Meanwhile, the suburbs of London, or the majority of the parishes outside of the London wall, remained untouched by the fire and by newer architecture. These parishes in the suburbs also happen to be among the poorer parishes of London at this point, especially to the east of the city (Mortimer 2017, 29). The combination of older buildings and a lower socioeconomic status made these parishes more vulnerable. This can be seen in the maps where the highest number of recorded deaths occured in the parishes further away from the city center, such as St. Dunstan at Stepney, St. Andrew Holborn, and St. James in Westminster. Further, St. Andrew Holborn and St. James in Westminster were some of the parishes that had deaths recorded in both week 50 and week 51 of the Bills of Mortality. Parishes that had deaths recorded in more than one week might mean that these were the areas hardest hit by the hurricane, or saw the most destruction, if our theory about printing delays stands. If a particular parish was harder hit by the storm, reporting the number of dead in their parish in time for printing the weekly bills might not have been a priority, or it was not possible to find the victims in time for the deadline.

Hurricanes hitting the British Isles are not common, but they do happen. Even today with the up to the minute information that is available to us through technology, getting accurate information during a natural disaster is difficult and not always reliable. Working with historical storms only compounds that difficulty. But the Bills of Mortality offer us a window into both the impact of the storm on the city as well as the aftermath and early modern reporting of storm deaths.

Works Cited

Daniel Defoe. The Novels and Miscellaneous Works of Daniel Defoe, Volume 6. Henry G. Bohn, 1855. Accessed July 29, 2022. http://archive.org/details/novelsandmiscel15defogoog.

M.D. A word in season to the nation in general. London: J. Nutt, 1703.

Mortimer, Ian. The Time Traveler’s Guide to Restoration Britain. First Pegasus Books hardcover edition April 2017. New York, N.Y.: Pegasus Books Ltd, 2017.