| July 5, 2022

The Parish Clerks' memento mori: Iconography of Death and trademark in The London Bills of Mortality, 1727-1752

In the fourth week of 1727 the habitual readers of the Bills of Mortality noticed something different in the most recent bill. The bill printed on Thursday January 9th showcased a border of skulls and crossed-bones framing the death counts in both the verso and the recto.1 The artwork of the skull was fairly simple: a bike-seat-like cranium slightly bent to the right, with triangular nostrils, three ovals as eyes and mouth, and two crossed-bones at the bottom.

Apparently, it took Will Humphryes –the Printer to the Company of Parish Clerks– a few weeks of trial-and-error with the woodcut blocks to set the final outline of the skull rim. Humphyres initially placed the skulls side by side, facing symmetrically to the center of the bill. One week later, the skulls on the side were facing down, vertically piled up on top of one another, while the top and bottom stripes remained facing inwards. Six weeks later, in the bill published on February 24th, William Humphryes placed the skull and crossed-bones border in what would become their permanent display: all skulls pointing downwards, both in the horizontal and vertical rims.

Figure 1. 1727, 3rd week, skulls facing inward

Figure 2. 1727, 4th week, skulls facing downwards

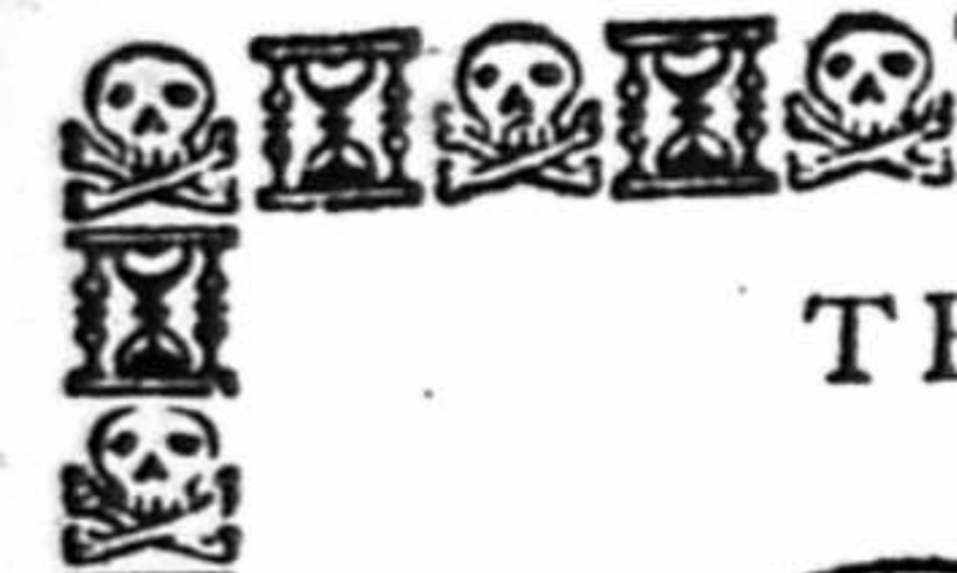

The skull and crossed-bones border remained untouched for more than sixteen years, until August of 1743, when Humphryes and the Parish Clerks decided to give the artwork an update. The bill published on August 11th, corresponding to 1743’s thirty-fourth week, included a more complex framing made of a sequence of a skull and the frontal view of an hourglass, set in an intercalated fashion. Adding the hourglass was not the only innovation, though. The shape of the skull printed by Humphryes in 1743 was quite different from the 1727 version. The fully frontally placed skull had a smaller cranium, and it included the remnants of a maxilla or upper jaw on top of slightly thinner crossed-bones. Although William Humphryes’ name was removed from the Bills of Mortality by 1749, the skull-hourglass fringe kept showing up at least until late 1752 (which is the final year of the Death by Numbers project).

Figure 3. 1743, 34th week, updated design including an hourglass

What possible interpretations can we draw from the iconography of death inscribed on the Bills of Mortality? For the average eighteenth-century Londoner, witnessing such stereotypical representations of death in a printed publication about death was probably of little surprise. Skulls, hourglasses, shovels, scythes, weeping puttos and skeletons were commonly included and adapted to fit in printed funeral invitations and publications surrounding the rituals that dealt with the deceased.

This repertoire of motifs, figures and patterns formed the visual language of the memento mori tradition, a symbolic trope that stresses the impermanence of life, and reminds mortal beings that death is “ready to strike anywhere at a moment’s notice”.2 As Malcolm Jones suggests in The Print in Early Modern England, ephemeral publications of a “passing nature” like the Bills of Mortality and “[p]lague broadsides listing the number who had died” would be usually framed with “conventional funereal images” and the visual vocabulary of the memento mori.3

But Londoners’ acquaintance with the Early Modern imagery of death did not imply that the meanings of death were historically fixed. In his classic study Western Attitudes Toward Death from the Middle Ages to the Present, Philippe Aries argues that between the sixteenth and eighteenth-century a slow but steady transformation disrupted the cultural understandings of death. According to Aries, death became “increasingly thought of as a transgression which tears man [and woman] from his[/her] daily life”.4 The rituals of death moved from banal and customary life matters, to breaking points capable of casting individuals “into paroxysm (…) into an irrational, violent and beautiful world”.5 By the late eighteenth-century Western rituals for the deceased would be “inspired by a passionate sorrow which is unique among sorrows”.6 Death became “Thy Death”: the death of another, the passing away of the beloved.7

But there’s no need for overinterpretations or getting too deep into the mentalités. A lighter reading of skull-hourglass framing might have to do with the inner workings of the printing industry in Early Modern London. According to Nigel Llewellyn, improvements in printing techniques in the mid eighteenth-century made possible the functional and –most importantly– cheap inclusion of memento mori’s iconography into prints of a short-lived nature.8 Llewellyn explains that a “relatively sophisticated but non-specific design” - could be “simply and quickly adapted for a particular occasion” in order to meet the demands of the growing funeral and undertaking service business.9 As Stephen Greenberg points out, by the late seventeenth century several printing “strategies evolved to make the mortality figures available as quickly and widely as possible”.10 These strategies included leaving valuable types “standing week after week” and the use of “multiple presses” to secure the publishing schedule.11 In any case, the inclusion of death’s imagery in the bills did not interrupt the end-to-end information pipeline: a workflow that started with the deployment of the “searchers of the death” gathering street level information and delivering it to the Company of the Parish Clerks, who were in charge of arranging the weekly figures and tables that William Humphyres would print.

It could be also possible –and this is pure speculation– that the skull-hourglass framing was a watermark added to the London Bills as a sort of a copyright. A way to guarantee that these were the official mortality figures gathered by the Company of the Parish Clerks, and a trademark that allowed Londoners to double check the legitimacy of the Bills being sold for a penny in London’s bookstalls. As Sheila O’Connell points out, “printmaking is essentially an urban and commercial phenomenon; it developed to serve the needs of a population which was congregated in towns”.12 Either as branding or as reminders of human mortality, skulls and hourglasses decorating official public health documents are more surprising to modern eyes than the people back then in eighteenth-century London.

The dates in this blog post are estimated based on the dates originally printed on the bills, which correspond to the Early Modern calendar usage. No adjustment has been performed on the dates to account for modern calendars. For more information on the calendar confusion, see our recent post on the topic. ↩︎

Nigel Llewellyn, The Art of Death: Visual Culture in the English Death Ritual c. 1500-c. 1800, (London: Reaktion Books, 2013), 25. ↩︎

Malcolm Jones, The Print in Early Modern England: An Historical Oversight (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 271. ↩︎

Philippe Ariès, Patricia Ranum, Western Attitudes Toward Death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Vol. 3. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), 57. ↩︎

Aries, Western Attitudes Toward Death, 57. ↩︎

Aries, Western Attitudes Toward Death, 59. ↩︎

Aries, Western Attitudes Toward Death, 68. ↩︎

Llewellyn, The Art of Death, 75. ↩︎

Llewellyn, The Art of Death, 75. ↩︎

Stephen Greenberg, “Plague, the Printing Press, and Public Health in Seventeenth-Century London”. Huntington Library Quarterly, 67, no. 4, 67, (2004): 525. ↩︎

Greenberg, “Plague”, 526. ↩︎

Sheila O’Connel, The Popular Print in England: 1550-1850, (London: British Museum, 1999), 11. ↩︎