| June 20, 2022

Strangled himself (being distracted): Messy Data and Suicides in the Bills of Mortality

Content Warning: This post contains subject matter that some may find sensitive or disturbing, be advised. If uncomfortable with this topic, you may support Death By Numbers in other posts.

This blog post will be a bit different than a few of our previous posts. Now that we have discussed our project workflow, we are going to begin to discuss the content of the Bills themselves. One thing that we immediately noticed on beginning this project is that suicides are reported on the Bills in a variety of ways that lead to more questions than answers regarding the weekly suicide rate in London. The variety of reports had a lot to do with the religious and legal views on suicide in this era.

When looking at suicide rates, Sleepless Souls by Michael MacDonald and Terence R. Murphy state in Table 7.1 Sex Ratio of Selected Groups, 1485-1714, that male to female suicide was in a range of 4 to 7.5:1 in the large of England. He compares that to suicides in the Bills, which is London focused, that still hold a male to female rate of approximately 1.8:1. That is a wide gap of information to be working with and there are quite a few reasons for this.

Suicide or Self-murder?

To start off, the word suicide is a recent addition to the English language. The Oxford Dictionary places it first appearing in Religio medici by Sir Thomas Browne in 1643. Before that addition, this action was called “Self-Murder.” Self-Murder was defined as a crime and sinful in the sixth century because it was seen as an act against God that one could not repent for.

When it came time to listing the deaths for the Bills, these suicide were then listed as other common phases of the time like “being a lunatick” or “being distracted.” The reasons for the different listings comes from the lack of understanding of why suicide was attempted and many authority figures feeling it was a rejection of religion. In Lunatics and idiots, Peter Rushton discusses mental disability and what we know now as mental health in this time. He finds that being defined as a lunatick or distracted was used when the individual in question was a harm to themselves or others.

Since self-murder was outlawed, this also changes how we view when or where someone died as listed in the Bills. Many family members still wanted their loved one to be buried in a respectable fashion, so there most likely an incentive to have the death listed in a different manner. This could include calling the death an accident.

How to define what is and isn’t an accident

The numbers and stories collected in the Bills has affected the history of London because there were areas of the city more infamous for suicide and death than others. On page 30 in Peter Ackroyd’s London Under: The Secret History Beneath the Streets he states “The suicides of the city were, until 1823, buried at a particular crossroads that exists still at the junction of Grosvenor Place and Hobart Place; it may therefore be deemed to be an unlucky spot.”

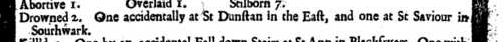

That coloured past makes parts of the Bills easier to section out deaths that were an accident versus purposeful actions. For most data in the process, we have to look for certain word choice that we know means suicide. That means we only account a death as a suicide, not an accident, if it says being a lunitick, being distracted, or some other language similar to that. However, defining suicide becomes even trickier when looking further into deaths classified as drownings. In the example pictured below, one drowning is stated as being an accident while the other just states where the drowning happened. Does that mean that the second one was a suicide, a killing, or another accident? Without having access to more detailed records that may be in London, we can’t know.

Our team decided it was best to put all drownings in their own category to limit our after-the-fact interpretation of the data. If we spent the time trying to find the documentation to every drowning, this project could take years and might still never be accurate. In the case of the drowning below, we cannot tell if this is suicide, so it will fall into our “drowning” category for consistently.

Figure 1. Bill of mortality snippet reading: Drowned 2. One accidentally at St Dunstan in the East, and one at St Saviour in Southwark.

Other works involving the Bills

We have seen interesting, and sometimes confusing, information in the Bills about suicide, but there are authors who have done great work to analyze these numbers even further. I previously mentioned Sleepless Souls above, but the authors do a deep dive into suicide versus self-murder and how that related to society. The authors use the Bills as a secondary focus while the rest of the book handles various amounts of multifaceted issues within that discussion and puts statistics and data behind it.

Then, a more recent addition from 2016 is Accidents and Violent Death in Early Modern London: 1650-1750 by Craig Spence. Spence takes a look at all the information he could find from the Bills as a primary focus and saw a similar outcome with suicide statistics. He corroborates on page 36 that in London alone, that male suicides were generally higher than women’s, about 1.6:1. This is still close to MacDonald’s 1.8:1. Accidents and Violent Death resonated with our team because it was a similar primary focus we are aiming to give the Bills plus an interesting stance comparing the statistics to the social stigmas of the time. Women of this time were deemed as more emotional and, more often labeled, hysterical. Meanwhile, it seems men were also struggling mentally and emotionally.

The history of London still has so much left to be uncovered and discussed. As our team and others look through the Bills, we hope to answer questions and better understand where we come from. Mental health and disability history are becoming more widely studied by historians and we hope that as we process this messy data, we can portray the most accurate picture of Early Modern London.

Also thankfully today there are more discussions and resources available to people struggling. If you or someone you know is thinking about suicide, or if you need someone to talk to, here are some places to reach out to.

For the US: National Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone number is 1-800-273-8255 which will simply be 988 after July 16, 2022. There is also an Online Chat or a Crisis Text Line: Text “HOME” to 741741

For the UK: EU Emotional Support Helpline is 01708 765200

Shout Crisis Text Line: Text “SHOUT” to 85258

The NHS has a larger list of wider resources here: Phone a helpline