| March 28, 2022

A Parish By Any Other Name

The Bill of Mortality from Christmas week in 1664 reports that three people died in the parish of St Foster. But fifty years later, there were happily no Christmas deaths in the parish of St Vedast—or rather, the parish of “St Vedast alias Foster.” Because the parish of St Vedast is the parish of St Foster. Welcome to the complex world of early modern parish names.

Given that our sources were published over the course of centuries, it’s hardly surprising that the names of some of the parishes in the bills changed over time. It does, however, present a bit of a challenge for our project since transcribers must be able to match the names in the bills to the names on the transcription form. And even if we were to change the names on the transcription form to accommodate changing parish names, analyzing bills of mortality over time still requires us to know whether a parish listed on a bill in 1582 is the same as a parish listed in a bill in 1752. Our solution has been to create a master list of the parish names, which includes the parish names we use on the transcription forms along with variant names that transcribers might encounter over time. These variant names are then included both in the transcription form and the detailed guidelines for our transcribers.

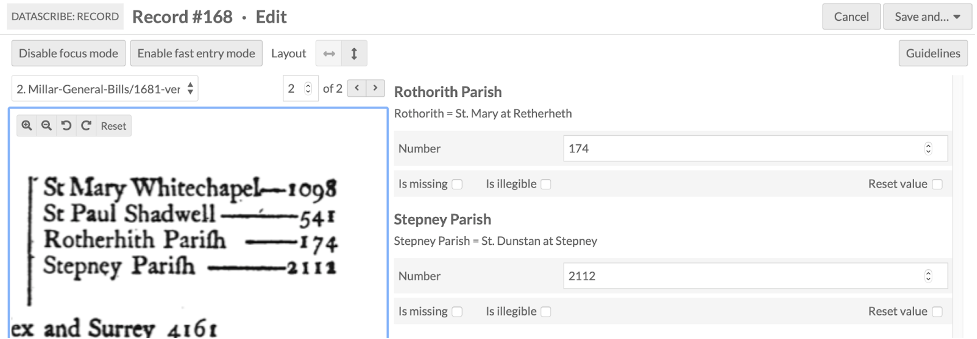

Figure 1. Image of the DataScribe interface showing Rothorith and Stepney parishes along with alternative names St Mary at Rotherhith and St Dunstan at Stepney.

In tracking how parish names changed over time, it immediately becomes clear that these changes were not generally the result of official parish name changes. Instead, they frequently resulted from changes in what the people who lived in London at the time called the parishes, instances when the everyday name of a place did not match the official record. This sort of change happens even today—places are known by nicknames or shortened forms instead of their official titles. People call The Metropolitan Museum of Art “The Met.” Her Majesty’s Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London is usually just “Tower of London” or even “The Tower”.

The most straightforward of the parish name changes are the ones which resulted from administrative changes. For example, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the parish of St Mary Savory split into two parishes: St Mary le Strand and the Precinct of Savoy. Around the same time, parts of the parish of St Martin in the Fields split off to form new parishes as the population rose in Mayfair and the West End, thanks to the creation of fashionable neighborhoods for the elite.

Some of the parish nicknames are also easy to figure out, at least if you’re familiar with early modern English. There are multiple parishes which vary between being a “St Mary Magdalene” and “St Maudlin”—“maudlin” being an English mushing-up of “magdalen”. (And yes, that is where the modern meaning of “maudlin” comes from. St Mary Magdalen was often depicted weeping.) Similarly, St Augustine was commonly abbreviated St Austin, St Anthony became St Antholin, and St Bridget became St Bride.

Parish names also varied by including something about the location of the church which served as its anchor. So All Hallows the Less was also known as “All Hallows upon the Cellar,” because it was built over the vaults of a cellar, and as “All Hallows near the Ropery,” because the parish was near the Thames in a part of the city where rope was made. People would also use street names or a general location to help identify a parish, which was useful in a city where many of the parishes shared names. You could make sure someone went to the right St Olave by telling them to go to St Olave Silver Street, not St Olave in the Old Jury or the St Olave in Southwark. It would also help you distinguish between the many St Michaels within the city walls: Were you looking for the one in Cornhill, on Wood St, in the Querne, or the one on Crooked Lane also known as “towards the Bridge”?

These geographical distinctions also helped when a new church with a similar name was added to the Bills. For years, there was only one Christ Church in the parishes in Middlesex and Surrey. When Christ Church Middlesex was established in 1729, however, the Bills started listing the older parish as “Christ Church Surrey” in order to keep track of which was which.

Not all of the changes in parish names are so easy to follow, particularly those which were the result of a linguistic shift instead of a clarifying geographic addition. One that routinely trips up new transcribers is St Vedast aka St Foster. According to the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks, St Vedast was a French saint. The name in England evolved through “Vastes, Fastes, Faster and Fauster to Foster.” Some of the Bills helpfully listed the parish as “St Vedast vulg. St Foster.” Vulg is short for “vulgar” which in this case didn’t mean rude but “commonly known as.”

While we can usually uncover which parish is meant by a new name in a Bill, we’ve found at least one mystery. The parish of “St Nicholas Willows” popped up in an early published bill from 1582. Stowe’s London Chronicles name it as a parish under Edward IV, but without any clear idea of where exactly it was. Two of the other St Nicholas parishes in London—St Nicholases Acons & Cole Abbey—are listed in the 1582 Bills, so these can’t be the Willows. We think it must be St Nicholas Olave, which had already appeared in a surviving 1562 bill as “Nycholas Ollyve” and appears again in a 1591 manuscript bill, alongside the other two St Nicholas parishes. But we haven’t yet found definitive proof.

As you can see, there are a lot of variations to keep track of when working with the Bills. The canonical parish name list we created thus allows us to standardize the data we generate from the Bills across the centuries, both in data exports and in the exploratory tables on our site (forthcoming). Our internal reference list includes the primary name we’re using in our transcription forms, with additional columns for name variations, first date in the Bills, and internal notes. We have also cross-referenced this list with the names for these parishes in two key sources: the list of parishes from the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks and the Map of Early Modern London. Tracking how our canonical names correspond to these sources’ will help us create crosswalks between our data in the future. Because a parish by any other name is still the same place.