| February 28, 2022

Parishes and Extra-Parochial Places

The main organizational unit behind the London Bills of Mortality is the parish: a religious administrative unit usually consisting of one or more churches, their associated staff, and all Christians living within the geographical bounds of the parish. The parish clergy christened, married, and buried their parishioners and—starting in the sixteenth century—the parish clerk kept a register of those events. The burial numbers would eventually form the basis of the bills, with christenings added later.

Most of London’s parishes were founded by the late medieval era, though the city’s parish landscape went through a series of small changes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Most strikingly, Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries meant that several previously private monastic, priory, and hospital churches were repurposed as parish churches, in new parishes created for the city’s inhabitants. St. Bartholomew the Great, St. Bartholomew the Less, and Holy Trinity Minories were part of a dissolved priory, refounded hospital, and dissolved nunnery, respectively, and were all refounded as civil parishes in the mid-sixteenth century. Numerous parishes were also destroyed during the 1666 Great Fire of London and only slowly reconstituted over the following decades. There were also a larger series of expansions of London’s suburban parishes in the eighteenth century. A striking example is the partitioning of St. Dunstan Stepney, which spun off five daughter parishes from 1719-1743. St. Andrew Holborn, St. Giles in the Field, St. Olave Southwark, and other parishes also divided in this period.

Of these changes, the most administratively significant was the reconstituting of monastic and other private churches as civil parishes during the Dissolution. This brought those churches and their newly formed parishes under the authority of London’s government for the first time. Until then, these churches and the areas surrounding them were extra-parochial places—that is, they existed outside the bounds of the parish system that covered the rest of the city. As such, extra-parochial places did not send their christening and burial numbers to the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks for inclusion in the city’s reports or Bills of Mortality.

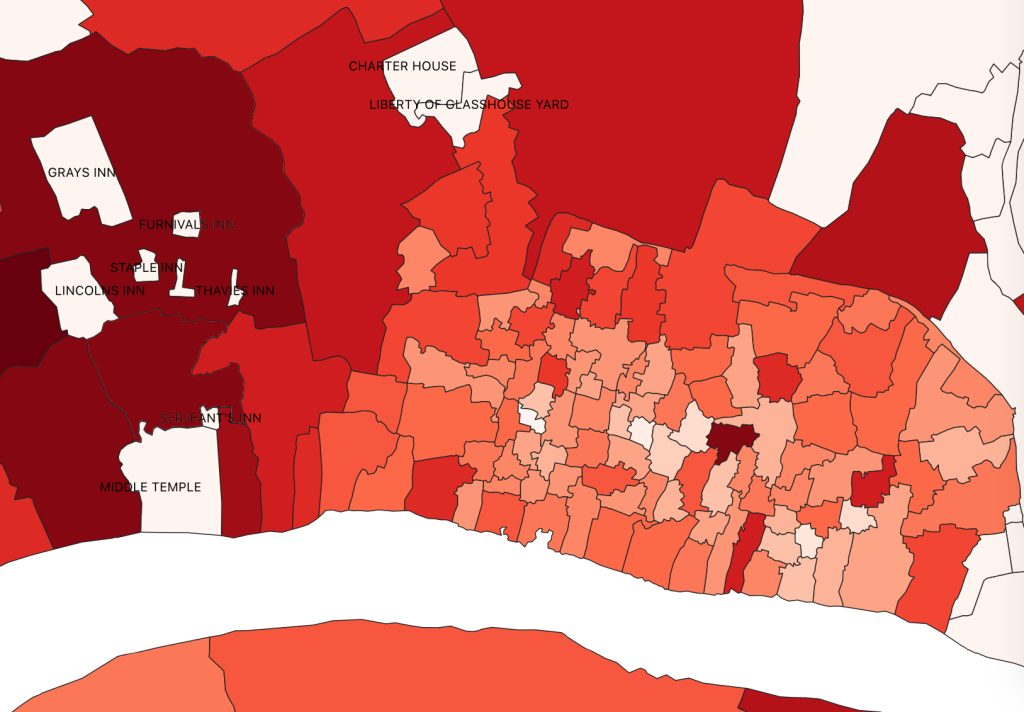

Figure 1. Map of London parishes showing several extra-parochial places in white.

However, the Dissolution did not remove all the extra-parochial places in London and several remained dotted throughout the city, most notably the liberties of the Inns of Court which included the former holdings of the Knights Templar. Charterhouse was an extra-parochial place, formerly a Carthusian monastery whose members resisted the Dissolution and died for it. The Liberty of Glasshouse Yard was also an extra-parochial place, established in 1601 under Queen Elizabeth.

The map above shows the parishes and liberties of London and is colored from dark red graduated down to pale pink based on the order of their first plague deaths during the 1665-7 epidemic. The extra-parochial places are colored white, not because there were no plague deaths there but because they did not report to the parish clerks and thus there is no data for them. (There was one parish within the walls of the city that reported no plague deaths and is also colored white but not labeled. The other large, central white space in the map is the river Thames). It is not shown on this map but, in a similar situation, the Tower of London was not included on the bills during this epidemic. Its parish—St. Peter Ad Vincula, where three queens of England were buried in the sixteenth century—occasionally appears on the Bills, but it was a royal peculiar and thus answered directly to the monarch rather than to the city government.

While the Bills of Mortality are a fabulous source of data about early modern births and deaths, they do have limits (which will continue to be discussed in future blog posts). The exclusion of extra-parochial places from the bills made sense from an administrative perspective during the early modern era, but does leave gaps in the dataset from a modern, data analytics and historian’s perspective. The geographical area covered by the bills changes over time and is not strictly coterminous with the city of London—however defined—during the early modern era. But the area covered by the bills was considered equivalent to the greater London metropolitan area, a subject which will be discussed more in our next blog post.