| February 14, 2022

Confusion of Calendars

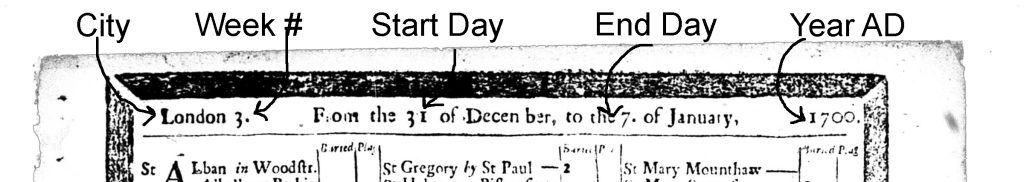

One of the first things a Bill of Mortality tells the reader is the date. The bill (partially) pictured below covers mortality data for the city of London, in the 3rd week of the current bills’ year, which ran from the 31st of December to the 7th of January in the year 1700 AD (from the Latin, Anno Domini, which was often translated into English as the Year of the Lord).

Figure 1. Annotated bill of mortality with arrows pointing to the city name (London), bill number (3), start and end days (‘From the 31st of December to the 7th of January’) and AD year (1700).

Bill excerpted from Paul Laxton, ed. The London Bills of Mortality, 1701-1829

For people living in early modern London, this was a straightforward and easily understood statement of the date. For the twenty-first century scholar, this is guaranteed to cause data problems if taken at face value and filtered through modern assumptions about time. First, the week of December 31st to January 7th was numbered as the third week of the bills’ years, not the first as we might assume from the inclusion of January 1st in this week. Second, the year 1700 AD applies to both the start and end day in this week; January 7th, 1700 came after December 31st, 1700 because New Year’s Day in the early modern English version of the Anno Domini calendar was on March 25th. And third, one even could go so far as to argue the date should be translated as January 10th through January 17th, 1701 because of later calendar reforms. The first line seen at the top of the bills– the deceptively and temptingly simple date–is hard to wrap our modern brains around.

The oddity of the numbered weeks are easiest to understand. Just as modern universities wrap up final exams in mid December before sending students off for the holidays, so too did the London parish clerks gather up the previous year’s data and produce yearly summaries in mid December. This is inconvenient for modern databases, as it prevents easy ordering of all the bills in one of our modern (January 1st-December 31st) calendar years by the week number. But 7-day weeks never divide neatly into 365- or 366-day years, meaning that the bills’ year could only rarely start on January 1st even if clerks had spent the 12 days of Christmas working to produce the annual summaries instead of celebrating. Some level of accommodation between the numbered weeks and a January 1st start date would have remained necessary. This accommodation sometimes led contemporaries to include 51 or 53 weeks in a yearly summary–another inconvenience for scholars attempting to impose temporal regularity on the dataset–but this was again a result of the uneven division of days in a year by weeks in a week and remains an issue to this day. Indeed, we just had a 53-week year in 2020.

Early modern England’s official use of March 25th as New Year’s Day is a bit trickier to deal with in the historical records, in part because many people informally adhered to a January 1st New Year’s Day instead . In fact, January 1st was the official beginning of the calendar year in Scotland starting in 1600. Many scholars silently “correct” the year for dates that fall between January 1st and March 24th to reflect a modern understanding of the start of the calendar year, while others adopt the early modern convention of split year notation, e.g. January 1st, 1700/1. For our project, we have chosen to retain the dates as originally printed on the bills in our transcriptions but label the years with split year notation in the metadata.

Lastly, while historians are rarely troubled by discontinuities in the calendar, it can cause major problems in quantitative analysis when a year suddenly has only 354 days. Our project has chosen to stop at the 1752 calendar reform to avoid the problem of this shortened year. But why did they change something as important as calendars at this time? Beginning in 1582, parts of Europe had abandoned the ancient Julian calendar, or Old Style, in favor of the newly created Gregorian calendar, also known as the New Style. The Gregorian calendar reform set the New Year’s Day to January first, skipped 10 days to compensate for centuries’ worth of accumulated error in the calendar, and adjusted the leap year so there was no extra day in years divisible by 100 (unless the year was also divisible by 400, e.g. 2000). While England initially refused to adopt the new calendar on religious and political grounds, by the middle of the eighteenth century the inconvenience of operating on a different calendar from the rest of Europe finally led to The Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750 and England’s adoption of the Gregorian calendar.

All this affects how we consider the weekly and annual bills. If someone is attempting to use formal datetime features of a programming language, they need to translate early modern English dates into modern Gregorian ones for accuracy. Someone attempting to use the built-in sort functions of spreadsheet software needs to determine how to input years so that the weeks are sorted in chronological order. And someone who is attempting to write about the dates on the bills, for an audience of modern readers, needs to determine the best way to clarify this confusion of early modern calendars.